Going deep on forgotten ‘Lakes of Washington’ books

Apr 25, 2024, 8:17 AM | Updated: 5:08 pm

With trout season opening on Washington’s lowland lakes this Saturday, April 27, the timing was perfect to go fishing around on the history bookshelf to share a prized catch – a forgotten encyclopedia of Washington lakes first published more than 60 years ago.

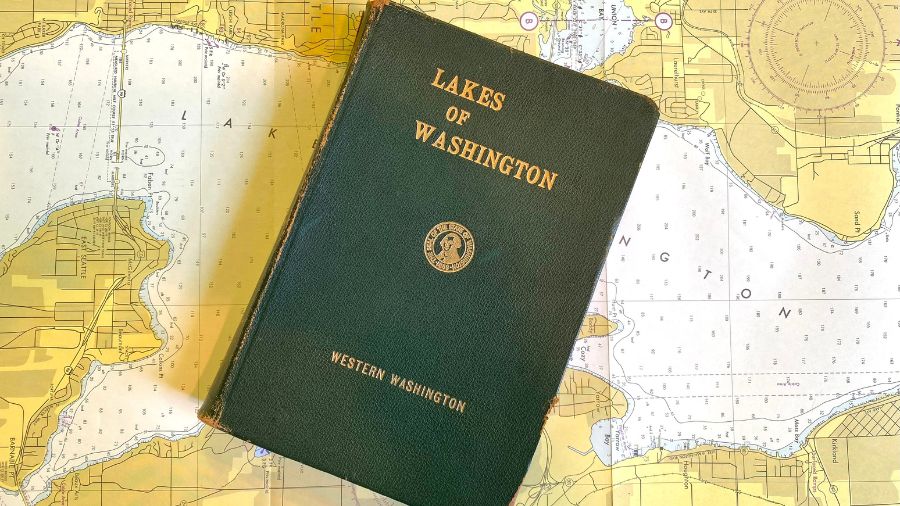

“Lakes of Washington” is a two-volume set of books published by the State of Washington through an agency that no longer exists called the Department of Conservation. There’s one volume for west of the Cascades, first published in 1961, and one for the east, originally issued in 1964. There are multiple editions issued in later years with revisions and changes to basic cover art. The book has gone through multiple bindings, including hardback and paperback.

At least one example, the 1961 first edition of Volume I for lakes west of the mountains, was issued in a green leatherette cover featuring gold-embossed lettering and matching state seal.

Inside all editions of “Lakes of Washington” are a ton of beautiful aerial photographs, rare maps and exhaustive vital statistics for thousands of Washington lakes – listing things like location, acreage and general descriptions.

More from MyNorthwest history: Echoes of Eastside rail history with Sound Transit preparing to get underway

Author and local legend Ernest Wolcott

“Lakes of Washington” is not an uncommon sight on the shelves of used bookstores in the northwest for years, but little, apparently, has ever been published about its origins. Some digging in newspaper archives revealed author Ernest E. Wolcott spent about 40 years as a civilian gathering information about Washington lakes because he loved to fish before he was hired by the State of Washington in the 1950s to translate all he’d compiled into an accessible format. Wolcott donated to the effort all the research materials he had assembled as an angler going back to the 1920s.

Along with competing in and winning a number of fishing derbies, by all accounts, Ernest Wolcott led an action-packed life throughout much of the first three-quarters of the 20th century.

Ernest E. Wolcott was born in Kansas in the 1890s and came to Washington as a teenager. As a young man, he became a maritime radio operator and was reportedly working in that capacity aboard a passenger liner called the SS Governor when it sank off Port Townsend in 1921. After joining the U.S. Navy sometime in the 1920s, Wolcott organized civilian emergency preparedness in the 1930s in Seattle by recruiting and managing a network of hams — amateur radio operators. He later had his own radio shop in Seattle, and served in the Navy during World War II, retiring as a captain from the Naval Reserves in 1954. Ernest Wolcott died, reportedly on San Juan Island, in early 1977 at age 78.

KIRO Newsradio reached out to multiple state agencies to see if the “Lakes of Washington” books were still remembered by anyone with a hand in water quality, fisheries or conservation. With help from the patient and indulgent communications staff, an employee of the Department of Fish and Wildlife was located who had bought copies of both volumes on eBay years ago. At the Department of Ecology, a senior environmental scientist named Will Hobbs reported that he had “inherited” multiple copies of “Lakes of Washington” when he moved into a particular office a decade ago, where he found the books on a shelf.

Legacy of the ‘Lakes of Washington’ books

“They’re pretty pristine, like they’ve sat on shelves for quite a while,” Hobbs told KIRO Newsradio earlier this week as he pulled one of the volumes from the shelf and examined it closely. “But there’s definitely some wear on the spine, (and) there’s usually a name crossed out, somebody else’s name.”

Hobbs continued, reading off two names of previous owners written inside the front cover.

“So it’s passed through at least three people’s hands,” Hobbs continued.

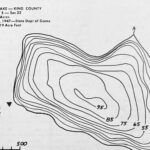

While Hobbs said he doesn’t consult “Lakes of Washington” on a regular basis, he does thumb through the dusty volumes on occasion. And he said the content within is still relevant, particularly the specialized maps that help scientists like him figure out where to collect core samples – from the deepest point – to understand the history of a particular lake.

“The material that’s contained within them, you know, it’s certainly still in use within our agency and within other agencies, too,” Hobbs said. “And in particular, the maps that are compiled – the bathymetric maps, the depth profiles of the lakes – are particularly useful.”

Bathymetric maps, Hobbs said, provided a distinctive understanding of the contours that are hidden below the waves of any body of water.

“It’s like an upside down topographic map right tells you tells you where the deep parts of the lake are and where the shallow parts are,” Hobbs said. “And in the old maps that are contained in these books, it’s all usually in 10-foot contours, so it gives you a great sense of the shape of the basin underlying the water surface.”

Sure enough, turning to page 170 of Volume I revealed a bathymetric map of Langlois Lake near Carnation in the Snoqualmie Valley, where many locals have fished, and where a Department of Fish and Wildlife boat launch and access point has been open to the public for decades. The map in Wolcott’s old book shows what many might find surprising: at its deepest point, the bottom of Langlois Lake is nearly 100 feet below the surface.

More from Feliks Banel: Banel’s ‘Scarecrow Video’ documentary nominated for Emmy Award

Hobbs said that many of the surveys required to produce the bathymetric maps in “Lakes of Washington” date to the 1940s, an era when gathering the required data was laborious and time intensive – likely using a small boat, and a weighted line which had to be dropped to the bottom in hundreds of spots to create a contoured profile of the lake bottom.

“They would have done transects, recorded them all and then drawn out the contour map,” Hobbs said, explaining that “a transect is a path from A to B. So it’s paddling across the lake, and then going a little farther and then paddling back across the lake, so they would have put as many lines across the lake as they could in the time that they had, recorded them, and then drawn it out.

“Of course, now we have all kinds of fancy equipment that we can send down autonomously, in some cases,” Hobbs said. “We zoom back and forth with a sound meter and get depth [data], and then we can map out the lake.”

Will Hobbs is a scientist focused on the microscopic world within the water and the core samples of Washington lakes, but he also clearly appreciates the scope and scale of what author Ernest Wolcott accomplished with these now nearly forgotten books.

Does perusing “Lakes of Washington” give Hobbs any sense of what “Ernie” (as Wolcott was known to his friends, and how he signed at least one copy of volume one) was like as a person?

“My first impression was that Ernie was a particularly meticulous personality,” Hobbs said. “I mean, you don’t compile something like this unless you’re really interested in the details of a lot of things, [so] that would be my first impression.

“To keep it going, too,” Hobbs continued. “I would think that he’s probably a stubborn person.”

Stubborn in a good way?

“Maybe I should change that,” Hobbs reconsidered. “We’ll call it dedication, dedication to the work.”

Ernest Wolcott’s descendants

Tracking down the family members of Ernest Wolcott was tricky. While Wolcott did have at least one son, he does not appear at this time to have any living direct descendants. Thanks to help from aviation and military historian Lee Corbin, KIRO Newsradio was able to connect with a woman from Hillsboro, Oregon named Shannon Walcott Cluphf whose grandfather was Ernest Wolcott’s brother (and who changed the spelling of his surname from “Wolcott” to “Walcott”).

“He was my father’s uncle,” Cluphf told KIRO Newsradio, referring to Ernest Wolcott. “I don’t know much, but what I do know is that he and my grandfather, who was Wallace Walcott, used to fish together within the Puget Sound and actually logged as well.”

As for changing the surname spelling from “Wolcott” to “Walcott,” Cluphf said she was told by her father that his father (her grandfather), “never liked the sound of ‘Wolcott,’ so he wanted ‘Walcott.'”

Cluphf also said her grandfather and her grandfather’s brother – again, that’s author Ernest Wolcott – had a falling out in the distant past.

“I think that there was a separation at some point, and my dad didn’t know much about it or what happened,” Cluphf said. “I remember him telling me that there was there was a separation. The cousins stayed close, but the uncles, his dad and his uncle, didn’t really stay close.”

Ernest Wolcott died before Shannon Walcott Cluphf was born, and her grandfather Wallace Wolcott also died decades ago. So when Shannon’s father died in 2016, it stirred up some deep emotions.

“When my dad died, I kind of had that moment of being like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m the last of the lineage and you know, what is there to really show for it?” Cluphf said. “I’m proud of my dad, I’m proud of my grandfather, but like, who’s going to know us?”

More from Feliks Banel: Layers of history revealed by ‘Street Trees of Seattle’

So, when a radio station from Seattle called to tell her about “Lakes of Washington” and to ask her questions about Ernest Wolcott, it came as news to Shannon Walcott Cluphf. It also made her feel pretty good to learn more about her Great Uncle Ernie and about his previously unknown-to-her legacy.

“I’ve heard of Uncle Ernie before, I just didn’t realize that he did all this amazing stuff and wrote books,” Cluphf said. “And I mean, that’s incredible to hear. And, if my dad were around, he would just be tickled pink. He would just be so happy to hear this.”

KIRO Newsradio will be sharing with Shannon Walcott Cluphf copies of the documents and newspaper clippings that were found as part of the research for this story.

And though Ernest Wolcott is not Will Hobbs’ “Great Uncle Ernie,” it said something about Wolcott’s long-ago masterpiece that a modern-day scientist can also appreciate “Lakes of Washington,” too.

Hobbs said that the federal Environmental Protection Administration conducted a national survey of lakes every five years, but he said it’s rare to have as grand and comprehensive an effort as what Ernest Wolcott did over decades of essentially volunteer work more than 60 years ago.

When it comes to monitoring and studying the natural environment, is this “Spirit of Ernie” – the meticulousness, the stubbornness, the dedication to the work – something worth resurrecting in 2024?

“I think so, yeah,” Hobbs said. “We all need to harness our ‘Inner Wolcott.'”

If you can’t find a hard copy of either volume of “Lakes of Washington,” Will Hobbs provided an update on Thursday to say that the entire contents are available online, with separate links for Volume I and for Volume II, as well as an additional link to an online database of other bathymetric maps of Washington lakes.

You can hear Feliks every Wednesday and Friday morning on Seattle’s Morning News with Dave Ross and Colleen O’Brien, read more from him here, and subscribe to The Resident Historian Podcast here. If you have a story idea or a question about Northwest history, please email Feliks here.